Photography has always morphed with technological advances, like the advent of the smartphone camera which revolutionised the photographic world. Featuring photographers Ben Lowy, Prarthna Singh and mobile photographers Eric Mencher, Glenn Homann and Dimpy Bhalotia.

Mobile photography turned 21 this year.

Yet, despite its ubiquity, many photographers deride it. They lug around heavy photo equipment as a badge of honour. When Pulitzer-winning New York Times photographer Damon Winter used Hipstamatic to take vintage-feel photos of soldiers in Afghanistan, he controversially won first place in Pictures of the Year International. It seems, for some, the iPhone and particularly the app didn’t meet unwritten standards expected of professional conflict photojournalism.

Photography has always morphed with technological advances. The advent of the smartphone camera was no exception. When cameras were introduced into the design of mobile phones, their popularity took off because of their ease of use and portability. They revolutionised the photographic world similarly to the way Kodak famously changed cameras from purely professional devices to amateur ones. Samsung in South Korea and Sharp in Japan both introduced the first inbuilt camera phones in 2000: just three years later, camera phones numbered in their millions around the world.

Like the first Leica camera, a design classic that brought enduring quality and sophistication to the market, the iPhone was a game-changer.

Designed from the outset with a camera, the iPhone’s connectivity and compatibility with apps set it apart from other mobile phones. Steve Jobs introduced the lightweight device in January 2007.

Mobile photography’s popularity soared in a flurry of innovation and developments around apps, most notably, the mobile photo-sharing app Instagram and the subsequent emergence of the “influencer”. Photography giant Annie Leibovitz famously touted the iPhone as the “snapshot camera of today”. When pioneering conflict photographer Ben Lowy covered wars in Afghanistan and Libya, like Winter, using a mobile phone and Hipstamatic, his photos from the latter featured in the NYT Magazine. On assignment for Time magazine, his images of Hurricane Sandy were the first phone shots to grace its cover.

Image: Ben Lowy, mobile photo of Hurricane Sandy used as cover for Time Magazine, 2012

Since those early years, smartphone cameras and associated technology have massively improved in every respect – lenses, sensors, image stabilisation, and so much more.

This continuing technological evolution is reflected in the competitions and prizes dedicated to mobile photography. Head On Foundation decided that the quality of mobile imagery had progressed to such an extent that it no longer needed a special category. A case in point, and a unanimous decision by the judges, 2020’s Landscape Award winner was this incredible mobile capture by Marcia Macmillan.

Image: Marcia Macmillan, Whimsical Warrior, Head On Landscape Award winner, 2020

Award-winning Australian photographer Glenn Homann, a long-time exclusive mobile user, agrees that the device used is less important now. He thinks there still needs to be space to celebrate the limitations of the devices but “…if a mobile image has the quality (both technically and aesthetically) to mix it with the ‘big boys’, then that is also something to be celebrated.”

Image: Glenn Homann, Corner, IPPAwards Abstract winner, 2021

Other recent mobile award-winners, photographers Dimpy Bhalotia and Prarthna Singh are both from India. Bhalotia, like Homann, captures exclusively with a mobile. She likes the unobstructed view and feeling in control of the device, capturing real-life moments as they happen on the street. For her, phone photography is freedom.

Inage: Dimpy Bhalotia, Flying Boys, IPPAwards Grand Prize Winner and Photographer of the Year, 2020

Singh, on the other hand, uses the camera that “feels right for that moment”. She enthuses that mobile photography has democratised photography, removing the need to invest money and resources into equipment, saying, “If you genuinely want to pursue a story, the equipment you use should not be the defining factor”.

Image: Prarthna Singh, Mother, PHmuseum Mobile Photo of the Year, 2021

Ben Lowy still uses his phone interchangeably with traditional cameras. Smartphones, he explains, offer more convenience in size and connectivity. Still, he sees no reason to segregate mobile photography from any other form of photography: they are all tools for telling stories. For Lowy, “Seeing is seeing, and vision is vision… mobile photography as a whole is less burdened by the weighty traditions and creative ethics of photography. One can edit images in real-time, use multiple filters and modes to aid in image creation – an instant darkroom in your pocket.”

Image: Ben Lowy from iStreet, Head On Photo Festival 2014

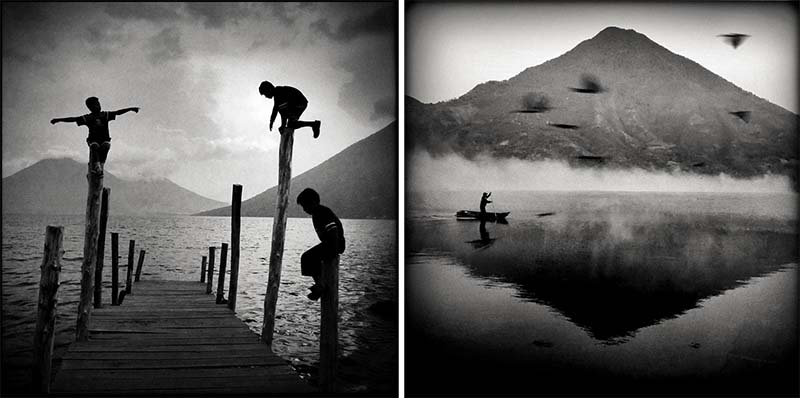

Eric Mencher, an ex-newspaper photographer in the US, sold his ‘proper’ camera gear and now shoots exclusively on mobile. He finds his phone camera visually liberating, more experimental. Mencher views the separation of mobile photography from regular photography as being primarily driven by assumptions on the part of curators, picture editors and creative directors that phones will only deliver low-quality photos. For him, a smartphone camera is just another tool in the photographer’s bag. He feels that this combination of new technology – smartphones and apps, has helped raise the quality of the work and inspired unique creativity. He credits Instagram as instrumental in democratising the art by removing “the traditional gatekeepers of photography”.

Images: Eric Mencher, from Guatemala

Edgar Gómez Cruz, an academic and senior lecturer in media (digital cultures) at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, has written extensively about mobile photography. He too feels that we should no longer separate mobile and regular photography:

“Some people even take it further, speaking, for example, of lens-based art or digital imagery rather than photography as such. What is photography anyway? (If you take the question seriously, you will see that it is not as easy as it seems.)”

He says while smartphone photography has democratised the industry, offering constant access to a camera, this switch from a Kodak culture to one of networked images has shifted the practice creating an emerging, innovative photographic environment, the future of which is algorithmic. Mobile photography could even be the purest form of the discipline since it frees photographers from technical considerations and allows them to concentrate on their vision, he adds.

A recent survey by Suite 48 Analytics shows that while 64% of surveyed professional photographers used smartphones for their personal use, only 13 % used them significantly for work. Reasons against included deficient features, lack of quality accessories, perceptions of their clients and some deeply rooted misconceptions about what sets a pro photographer apart from an amateur.

Yet, despite the naysayers and because of the excellent photographers who are drawn to it, mobile photography is here to stay. With the constant evolution of the technology, the question will soon be why more photographers and artists don’t pause before picking up a heavy DSLR and replace it with their phones.

Header image: Glenn Homann, Prune Deuce

About the author

Paula Broom is a writer and an environmental artist who works in sculpture, photography and installation. She works for Head On Foundation, writing for and editing Head On Interactional.

Photographers/Artists

Ben Lowy

Dimpy Bhalotia

Eric Mencher

Glenn Homann

Marcia Macmillan

Prarthna Singh