A survey from the earliest known First Nations photos through to modern-day Indigenous photographers who have greater control over the way their images are read.

In a 2009 photography supplement to Art World magazine, five Australian experts were invited to choose their favourite images. Two – NGA Curator of Photography, Isobel Crombie, and US Professor of the History of Photography, Geoff Batchen – chose 1847 daguerreotypes by Douglas T. Kilburn of the Kulin people in Melbourne, the earliest known First Nations photos. NSW Art Gallery’s Judy Annear selected the work of an unknown studio photographer around 1900, picturing a family group of equally unknown ‘Aboriginals’.

These Indigenous images may have been exotic curios for the local (and English) markets and weren’t ethnographic in intent. That would be the next trend. But however exploitative it might have seemed to bring Aborigines into a studio and pose them for the marketplace, what intrigues me are the comments of the three experts.

Despite a text by Kilburn “expressing the usual prejudices of the time”, Batchen believes “the gaze of these three figures has gradually taken on a potent symbolic power, silently confronting us with our collective responsibility for their people’s genocide.”

Douglas T. Kilburn, England, Great Britain 1813 – Hobart Town, Tasmania, Australia 10 March 1871

South-east Australian Aboriginal man and two younger companions

daguerreotype, 1/4 plate 8.0 (H) x 6.8 (W) cm (plate)

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra Purchased 2007 2007.81.122

”Who are the subjects?”, asks Annear. “Their engagement with the camera is complete.” For Crombie, “What I love is the strength and dignity of the women who engage the camera… speaking today about survival in a way that I find very moving.”

Later photographers – both white and black – would seek greater control over the way their images are read.

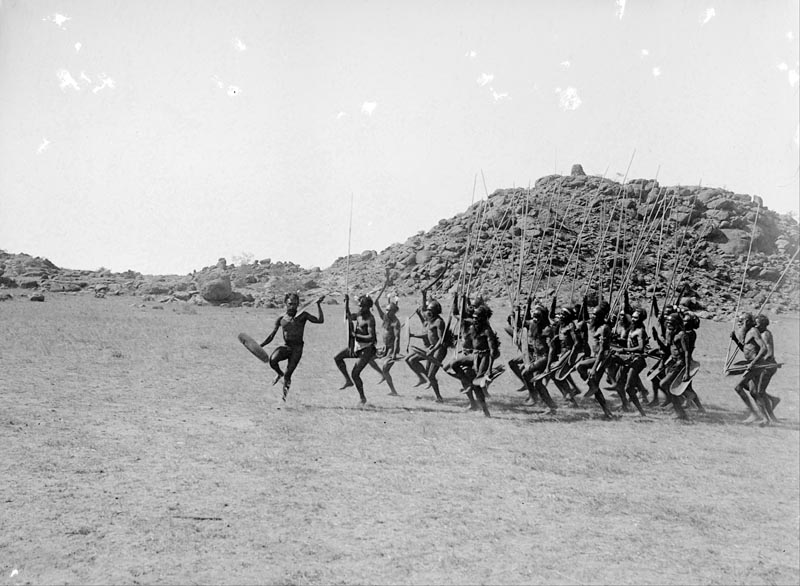

Another crucial figure was Walter Baldwin Spencer, travelling as a zoologist and photographer with the Horn Expedition to Central Australia in 1894. Spencer would continue filming Indigenous subjects until 1927, and with his Alice Springs partner, Francis Gillen, writing seminal books on Aranda ceremony and society. He and Gillen may have been trusted attendants at a four-month-long Engwura ceremony in the 1890s, but the resulting visual work is impersonal, an observer, not a participant.

Arrernte welcoming dance, entrance of the strangers, Alice Springs, Central Australia, 9 May 1901,

by Walter Baldwin Spencer and Francis J Gillen – Photographers

Details of artist on Google Art Project – VwEOf7R4tja73A at Google Cultural Institute maximum zoom level, Public Domain

To my knowledge, there have never been First Nations complaints about those images. But what can’t be ignored is that Spencer was a product of 19th -century social Darwinism – which, according to his fellow Protector of Aborigines, W. E. Roth, stated that “(a) in the struggle for existence, the black cannot compete with the white, and (b) with advancing civilisation, the black will die out.” His remarkable photographs, with careful commentary on the reasons behind each, are of immense value to his subjects’ descendants, but may be tainted in our eyes by that motivation.

Charles Mountford was not so fortunate. Despite more than 50 years association with Aborigines, and, clearly, much more engagement at a personal level with the subjects of his photos – most are named, for instance – his masterwork, Nomads of the Australian Desert, was banned in 1976 when Pitjantjatjara men took the publisher to court for revealing secret/sacred ceremonies and places. Ten years earlier, Mountford had had no problems with his Australian Aboriginal Portraits book, virtually a child’s guide to understanding the unknown ‘other’ in remote Australia. The book contains the note: “These sensitive studies are neither tourist poses nor anthropological records. They convey to the reader Mr Mountford’s own deep understanding of the real and endearing qualities of a people.”

Anthropologist Donald Thomson had the advantage of being sent into Arnhemland in 1933 to save the Yolngu from reprisals by a military expedition for a killing. The elder, Wonggu – photographed with seven of his twenty-six wives 1 – accepted that “Thomson had come to his Country with no desire either to make him work, to exploit him or to interfere in some other way with his way of life, or that of his people.” Included in the 1983 book, Donald Thomson in Arnhem Land, is Thomson’s photograph of goose egg hunters punting boats through a grassy swamp 2, an image that inspired the feature film, Ten Canoes.

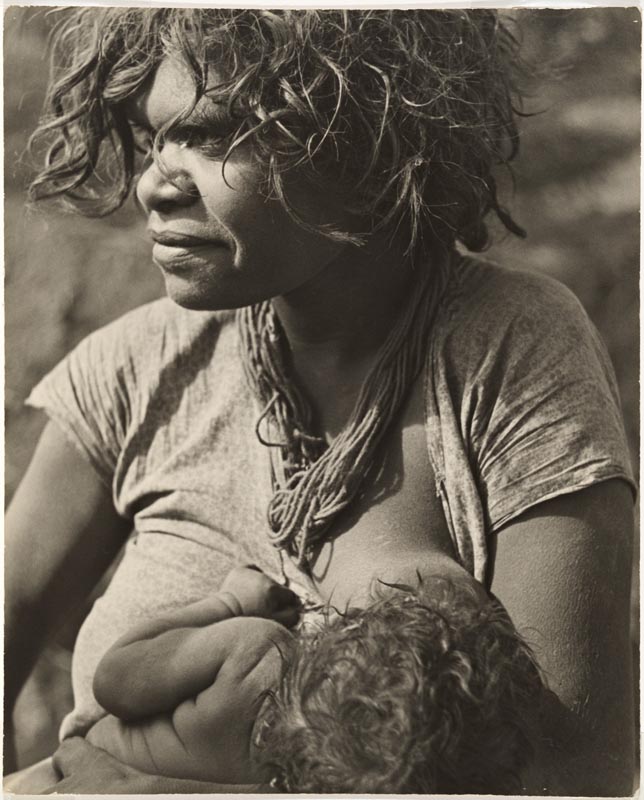

Post-war, Axel Poignant achieved similar rapport with Arnhemlanders in his work Encounter at Nagalarramba. Poignant’s reputation for sensitive Indigenous portraiture was sealed in 1947 when his religiously-titled Mary – capturing a relaxed desert mother feeding her newborn baby – won the gold medal from the Australian Photography annual. Ironically, its sunny setting disproves Poignant’s own caution: “The problem being that to get these people as they are, they are mostly in the shade of a bush-house or tree. Take them away and they no longer look natural.”

Axel Poignant, England 1906-1986 Mary 1942

gelatin silver photograph 50.2 (H) x 40.6 (W) cm (printed image)

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1984 1984.148

In the post-ethnological era, the emphasis in Indigenous photography has inevitably swung away from tribal Australia to the increasingly visible First Nations people in the cities of the south. As the Tent Embassy burst into life in Canberra in 1972, as Aboriginal Legal and Medical Services gained traction in Redfern, as the Aboriginal Islander Dance Troupe took flight, two non-Indigenous migrant women took their cameras into the urban Aboriginal scene: Juno Gemes from Hungary, and Elaine Pelot-Syron from the US. Pelet-Syron wanted to document what the Aboriginal community was achieving; “These were the years that the Aboriginal Medical Service started, and Isabel Coe and Jenny Munro started the Childrens’ Service”. Both photographers gave identity to emerging individuals like Marcia Langton and Mum Shirl.

Marcia Langton Illegal March, Land Rights before Commonwealth Games, Brisbane 1982 ©Juno Gemes

Courtesy of the artist

It was not until 1986 that Aboriginal photographers really took control of their own image-making. During NAIDOC week, on the raw brick walls of Sydney’s Aboriginal Artists Gallery, ten Indigenous photographers hung their work. They included Mervyn Bishop, Australia’s first Indigenous press photographer, Brenda L. Croft, Michael Riley and Tracey Moffatt. Ironically, Moffatt – who would later practice without identifying as Aboriginal – ruefully commented: “To be honest, we got the kind of publicity which makes me want to vomit; ‘They’re Aborigines, they’re articulate, and gee whizz, they take good pictures’ sort of stuff. I guess I shouldn’t complain because we got a lot of people coming through looking at the show and buying work.”

Much of this era would later be summed up in the NSW Art Gallery’s 2008 show Half Light : Portraits from Black Australia. Past efforts were dismissed: “The camera is the tool of a dominant society – the powerful photographing the oppressed.” But Indigenous curator Jonathan Jones found that “…despite the rich vein of self-representation, Indigenous Australia is still largely misconstrued. So, we’re working with portraiture to show the true face of our community, contradicting stereotypes.” The catalogue cover, for instance, featured Riley’s glamorous monochrome image of the young Moffatt, given startling blue whites to her fierce eyes. Croft, too, sought out female beauty to overcome memories of “the broken noble savage”. And Brook Andrew went hard for “the potency of blackness” (male).

Andrew, along with Christian Thompson and Michael Cook, would move on from the conventions of portraiture to add political, aesthetic and satirical elements to their photography.

In my view, the pre-eminent image-maker of this era is Ricky Maynard. The Tasmanian employs a documentary mode that responds to the historical depiction of First Nations people by engaging with their contemporary lives. Maynard has produced some of the most compelling images of Aboriginal Australia over the last two decades, often using his enviable collection of antique cameras. With them, he references great American social reformers such as Paul Strand, Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans.

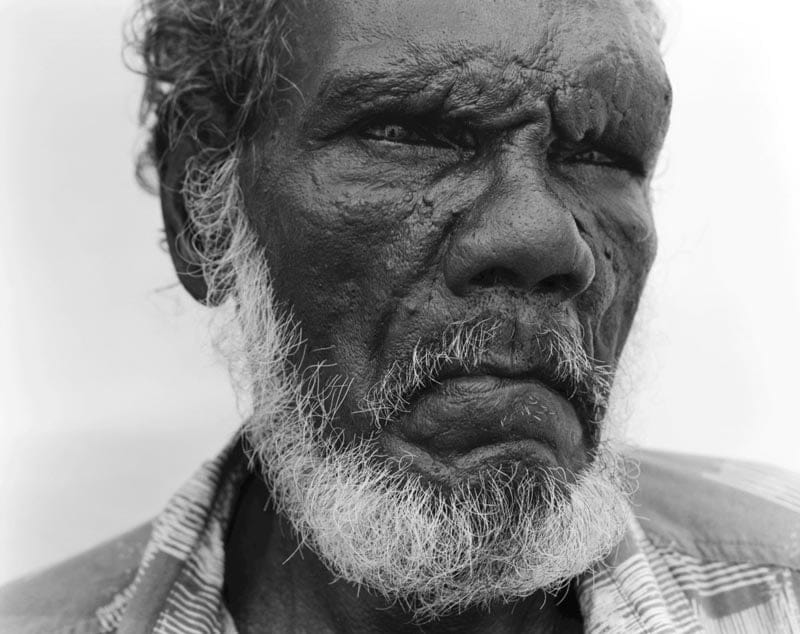

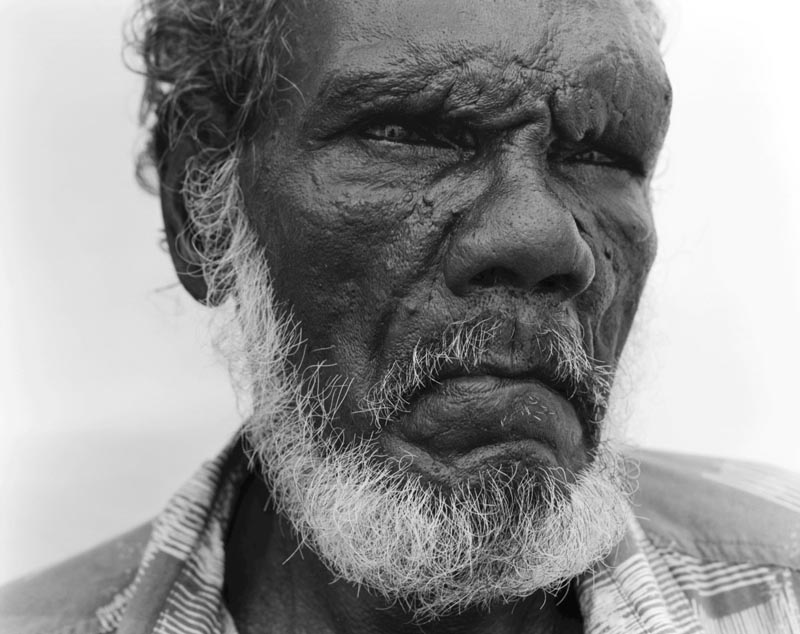

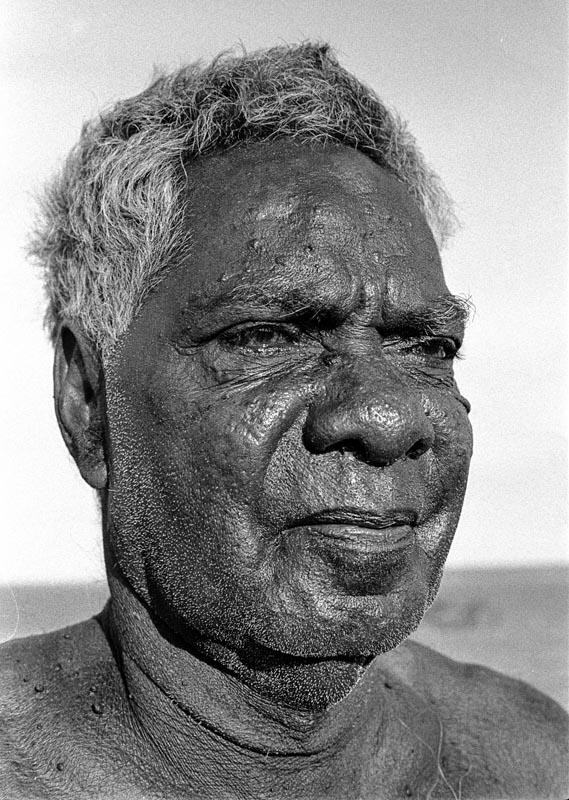

Maynard pursues the power of the uninflected image. His Moonbird Series self-portrait – standing in the Bass Strait waters, facing away and looking longingly (one imagines) towards the lost mainland of lutruwita – is as moving as anything in the Blak catalogue. Maynard commented: “I urge you, the viewer of my work, not just to look, rather, to see into the pictures and see this world as I show you now.” Later, he travelled to Cape York to capture the visages behind the seminal Wik Judgement in the High Court. His in-your-face close-ups of unsmiling Elders show every blemish of heroic lives, lived tough.

©Ricky Maynard, Wik Elder, Arthur

2000 Courtesy of the artist

Coincidentally, they brought to mind the almost-unknown work of white facilitator, Lance Bennett, whose important book on the bark artists of the North has only ever been published in Japanese. But the dignity in his closely observed faces is right up there with Maynard.

Lance Bennett, Namadbara, Croker Island, 1969

Courtesy of Barbara Spencer

[1] Donald Thomson’s image of Wonguu with seven of his twenty-six wives, 1933, can be viewed in a study guide here

[2] Donald Thomson’s image of The Goose Hunters of the Arafura Swamp, Central Arnhem Land, Australia, May 1937, is in the Thomson Collection with Museum Victoria but can be viewed here.

Header image: Ricky Maynard, Wik Elder Arthur, 2000. Courtesy of the artist.

About the author

A long-term commentator on the art and culture of First Nations Australia, Jeremy Eccles took his first photos of the Indigenous at the 1985 Groote Eylandt inter-tribal dance festival. He has written extensively on First Nations artists. In 2021, Jeremy was elected to a Fellowship of the Royal Society of New South Wales for his services to the understanding of Australian Indigenous art and culture.

Photographers/Artists

Douglas T Kilburn

Walter Baldwin Spencer and Francis Gillen

Axel Poignant

Juno Gemes

Ricky Maynard

Lance Bennett

Charles Mountford

Donald Thomson

Elaine Pelot-Syron

Mervyn Bishop

Brenda L Croft

Michael Riley

Tracey Moffatt

Brook Andrew

Christian Thompson

Michael Cook