Warning: this article contains war and conflict imagery that some readers may find confronting.

TM: What’s the difference between covering ISIS in Iraq and covering Ukraine?

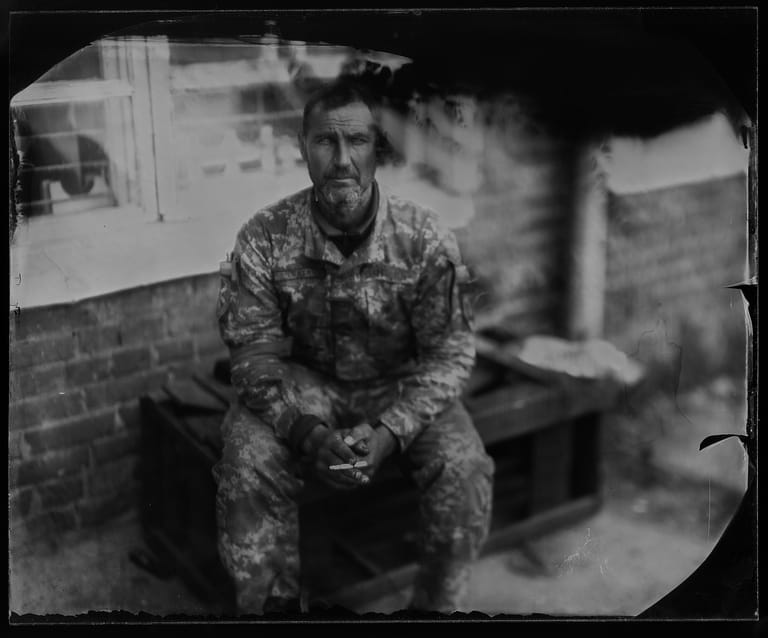

IP: Ukraine is a much higher level of risk. War zones like Mosul were dangerous for sure, you could get into quite difficult situations going in with assaulting units, but you were with a much better-armed side, and with American planes overhead. I felt much more comfortable covering Mosul than I do in the Ukraine conflict. It’s a brutal war with two very well-armed forces going up against each other. That makes it entirely different from anything my generation of conflict photographers has covered in the last 20 or 30 years. Plus, we’re on the less well-armed side, which makes it really tricky on the frontline.

“I felt much more comfortable covering Mosul than I do in the Ukraine conflict. It’s a brutal war with two very well-armed forces going up against each other.”

TM: Does it take any readjustment in thinking about how you get the shots?

IP: It comes down to the same things you’re looking for, but I’d say it’s harder to get to that critical point on the frontline where you can see the fighting going on, or seeing the effect the war is having on civilians in places like Bakhmut, where it’s just too dangerous to go in. Your decision-making as a war photographer is always limited by access and security.

TM: What was your first reaction when you heard the Russians had invaded Ukraine? Was it, ‘Great, here’s another story I can do’, or ‘Oh god, here we go again, more war…’

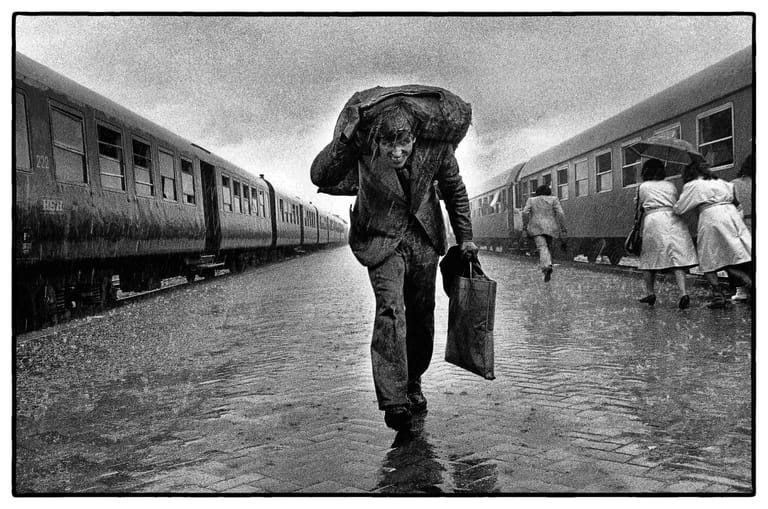

IP: I wasn’t that taken aback by the invasion. There’d already been a lot going on in eastern Ukraine in the previous six months or so before. And as an organisation (The New York Times) we were already accredited with the military and poised to go. I was ready to go in. I didn’t know what to expect, I don’t think anyone knew to what extent the Russians were going to invade. But it became quickly apparent it was a full-scale invasion. I was going somewhere I hadn’t worked before, so I was more nervous than I’d been for a while. Wading into an armed conflict in its first few days is unnerving. There’s always an exodus of people going out, and you’re going in, so it’s very disconcerting.

“I didn’t know what to expect, I don’t think anyone knew to what extent the Russians were going to invade. But it became quickly apparent it was a full-scale invasion.”

TM: What about your kit? What did you take into this war, other than the usual?

IP: For Ukraine, I basically had everything I needed and ready to go for a couple of weeks. The usual Canon 5D’s of course. Plus, I bought a few pairs of warmer socks! Made sure I had a lot of batteries and charges because the electricity supply could have been an issue. And a lot of dried food because we didn’t know what was going to happen, if there might be a siege-type situation in Kiev for example.

TM: And getting the images out to New York, is that difficult?

IP: If there’s no wi-fi in your hotel you can still hook up a hot spot to your cell phone and use that to send pictures. The connectivity has stayed pretty good, which is remarkable.

“The usual Canon 5D’s of course. Plus, I bought a few pairs of warmer socks!”

TM: Being with The New York Times, which is editorially pro-Ukraine in this conflict, are you in any way trying to show a side of the war that promotes Ukraine’s position?

IP: Inevitably I think we’re going to be aiding Ukraine by covering the war on their side. We have some people still working in Russia, but largely that’s gone. I would love to be covering this from the Russian side, I think it’s important if you can access things from both sides of the story. But that would be fraught, and difficult, and probably controlled, and your work would end up being propaganda. Of course, you can worry about that happening too with the Ukrainians. People in all wars complain about not getting access to the frontline, but when you get it, good luck – because you’re probably going to shit your pants! Access feels to me like you’re being forced into getting propaganda, whether you’re willingly doing it or not, because that’s what can happen in conflict reporting. Western militaries do this too, they show you only what they want you to see, and that doesn’t give the full picture. But I never feel like that’s really happening in Ukraine.

“People in all wars complain about not getting access to the frontline, but when you get it, good luck – because you’re probably going to shit your pants!”

TM: There’s a strong civilian side to the Ukrainian story. Has anyone ever tried to stop you working in that civilian environment, maybe suggesting you’re a spy?

IP: Yeah, I’ve had that situation, especially in the beginning. There was a lot more paranoia, uncertainty, and there were Russian saboteurs running around in Kiev.

TM: Now that you’re in almost constant contact with your office in New York, as compared say to those reporting and photographing the war in Vietnam in the 1960s – do you feel you can still be free to make your own decisions about where to go, what stories to cover, how to operate?

IP: We don’t get much direction from editors in The Times’ photo department. But the correspondents are more involved in directing coverage and coming up with the stories we’ll photograph. This war in Ukraine has been different for us as photographers in that there’s been constant updating on The Times’ website, and there’s obviously an endless need for content for that. So, as well as working on bigger stories which I want to do and have been able to do, we’re also being asked to file on a daily basis for live briefings, and that’s completely different from any big story I’ve worked on before with The New York Times. In Mosul I was on my own and I was writing, and I’d do the pictures and go off the grid for two or three weeks while I was working on my story, and then I would come back and say to New York, ‘I think I’ve got something,’ and then I’d put it all together.

“I’d do the pictures and go off the grid for two or three weeks while I was working on my story, and then I would come back and say to New York, ‘I think I’ve got something,’ and then I’d put it all together…”

TM: Did you ever think you’d be doing this work when you were studying photography in Newport, Wales? Is that what you wanted to do? Did you have war photographer heroes like Don McCullin?

IP: At the start in Dublin I was pretty raw and green. Once I began to study photography, I realised my interest was in conflict, not so much as a war photojournalist but more about the covering of the aftermath. And that’s where I went – to Serbia, Croatia – working with displaced people, and gradually I started to get closer to the actual conflict. And then in 2007 when the Arab Spring started and I was based in Beirut, it was just automatic. That’s when I started covering actual conflict.

TM: Your first real taste of war was in Libya. How did it feel being shot at?

IP: [Laughs] Looking back, crazy – driving down a highway with a ragtag group of rebels who’d started the uprising, and we were on the poorly armed side going up against a fully mechanised army. In the middle of the desert in open ground, we were getting shot at by tanks and planes. There was a degree of naivety in not understanding the dangers involved. Maybe that helps when you’re younger, I was only 27 then. But it’s the sort of bravery that’s not healthy.

“…driving down a highway with a ragtag group of rebels who’d started the uprising, and we were on the poorly armed side going up against a fully mechanised army.”

TM: What’s your formula for ‘when to stay, and when to pull out.’? Has it changed?

IP: It’s changing all the time. The frontline is changing, and the risks are changing, the level of fighting is changing, so you have to remain very capable of pivoting and reassessing everything on a daily basis. It’s always a team decision, with the photographer and the correspondent, the fixers and drivers – everyone has to be comfortable with being where you want to be to get the images. The main thing is letting everyone know that they have a voice, they can speak up and say ‘I’m not comfortable here.’ That’s really important because there’s a tendency to be scared to speak up because you don’t want to be the one to say you’re afraid and then feel like you’re ruining the job for everyone else. That doesn’t matter – because if you’re not sure and you’re nervous, that will cause you to make bad decisions. You always have to be switched on, to be ready, you’ve got to be up for it.

“…if you’re not sure and you’re nervous, that will cause you to make bad decisions…”

TM: You’ve covered a lot of conflict. What do you think it’s doing to you as a person?

IP: I think about it more the older I get and realise it’s taking something from me. And I’m constantly trying to keep an eye on that because I don’t want it to take away my chance at having a normal life, whatever that means. I do have a pretty normal life when I come off the story. I don’t have any children but I have a partner, and I have a really close relationship with my family and sisters back in Ireland, they’re incredibly supportive but they know the dangers involved and worry about me a lot. And I think that helps because if you don’t have contact with your family or they don’t give a shit about you, then there’s nothing to keep you in check. And that’s when people can go too far. I’ve definitely moved to the cautious end of the spectrum – having my family and my partner worrying about me, that helps keep me in check.

“…if you don’t have contact with your family or they don’t give a shit about you, then there’s nothing to keep you in check. And that’s when people can go too far.”

TM: The fact that Ukraine’s a war of attrition makes it hard to keep up not only your energy levels but also public interest in your work. Is there already a loss of interest?

IP: Yes, I’m sure there is, and I worry about that. It’s definitely getting harder to come up with new stories to tell, we’re left waiting for new breakthroughs, new areas to be liberated, and it’s very hard to time that, I don’t have much choice in where and when to go. I’ve found it getting more repetitive from a personal point of view, and if I start to feel that, as someone who’s engaged and interested in the story, then I know it’s ten times worse for the public.

TM: What about your view of humanity? It must be depressing to think this cycle of war you’ve covering is never going to end…

IP: It is depressing, and hard to maintain hope for us as a race. At the same time, you do see those moments of humanity, and maybe you hang on to them more than you would in other situations. With Ukraine for example, I’ve hated every moment of it because it’s such a stupid war and you want it to be over, but at the same time, I realise it’s again opened up this whole new place for me that I didn’t know. It’s an incredible country. As with any conflict, you get to see the worst and best in people. The Ukrainians are incredibly tough, there’s so much potential there, and that gives me hope. If they can get through this, I believe Ukraine is going to be a powerful country in the region, and in Europe.

TM: Do you have a plan for the future, beyond covering war? Or is it just one conflict after another?

IP: You go into the warzone for six weeks or two months and then you come home, and you don’t want to do anything else, to be honest for a month or so until you go back again. I’ve given it all my energy and attention, and I think it will be that way for the foreseeable. I’m not just a war photographer, I’ve always said that. I’m essentially concerned with human life, stories about people, the environment, I can throw myself into anything. I want to be involved in covering the biggest stories we’re facing. I hope it’s not only that I’ll be covering conflict and jumping from one conflict to the other.

“I’m not just a war photographer, I’ve always said that. I’m essentially concerned with human life, stories about people, the environment, I can throw myself into anything.”

Ivor Prickett

Growing up in Ireland, Ivor Prickett gained his degree in Documentary Photography at the University of Wales Newport, and freelanced for three years in London before heading off to the Balkans to photograph the aftermath of conflicts there.

Based in Middle East since 2009, he documented the ‘Arab Spring’ uprisings in Egypt and Libya, working simultaneously on editorial assignments and his own long-term projects. On the road between 2012 and 2015, he photographed the Syrian refugee crisis, working closely with UNHCR to produce a comprehensive study of the greatest humanitarian crisis in recent history. He’s currently covering the Ukraine conflict for The New York Times.

Prickett’s photography has appeared in other major magazines and newspapers including The Sunday Times Magazine, Telegraph Magazine, Stern, GEO, and National Geographic. His conflict work in Iraq and Syria has earned him multiple World Press Photo Awards and in 2018 he was named as a Pulitzer finalist. The entire body of work titled ‘End of the Caliphate’ was released as a book by renowned German publisher Steidl in June 2019.

Ivor Prickett’s images have been exhibited widely at institutions such as The Victoria and Albert Museum, Sothebys, Foam Gallery and The National Portrait Gallery London. He is represented by Panos Pictures in London and is a European Canon Ambassador.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tony Maniaty is a Sydney and Paris-based photographer, author and journalist, academic and reviewer who works across a broad creative canvas. He is the features editor for Head On Interactional.

0 Comments