Bombay Wall: Joseph McGlennon

Mark Kimber examines the work surrounding Joseph McGlennon’s portrait which hung as a finalist in the 2011 Head On Portrait Prize. Entries for the 2012 prize close 11 pm March 11.

Within months of Daguerre’s 1839 announcement of the invention of photography, travellers had set off in search of their own discoveries carrying with them the new apparatus of photography. The 19th Century is synonymous with the concept of “discovery”, in the classic sense of the Western explorer journeying beyond the realms of “civilisation” and into the wild of the unknown. “Unknown” only to the West of course.

Indeed it was indicative of the arrogance of the West to assume the exotic East languished in some sort of cultural vacuum until it was given materiality by means of its exposure by Western explorers.

British photographers such as Captain Biggs had journeyed into India as early as 1850 to photograph ancient sculptures and inscriptions. And later Captain. E. D. Lyon in 1869 produced some of the finest photographic images of Indian architecture ever brought back to Europe.

The French too in artists such as Paul-Emile Miot played a vital role in what the photographic historian Francoise-Heilbrun called “photography’s part in the wonders of discovery”.(1)

Early photography did though have its limitations, certainly in relation to exposure control, which meant that photographers could not always capture all that was before them. The combination of land, sea and sky in one exposure was particularly problematic. Gustav le Gray in 1856 overcame these difficulties by combining multiple negs to produce stunning images of seascapes resplendent with stormy, cloud filled skies.

Throughout the 20th Century as camera technology and film stock improved it became much easier to travel with a range of efficient yet compact photographic equipment. At the same time though the West’s fascination with the exotic continued to burn brightly. And therein lies the problem.

To so much of the contemporary Western audience India remains, photographically, at least, exotic, different and enigmatic. It is possible to point a camera at virtually anything in India and produce an image, that to anyone living outside of the country, is compelling simply because it is different.

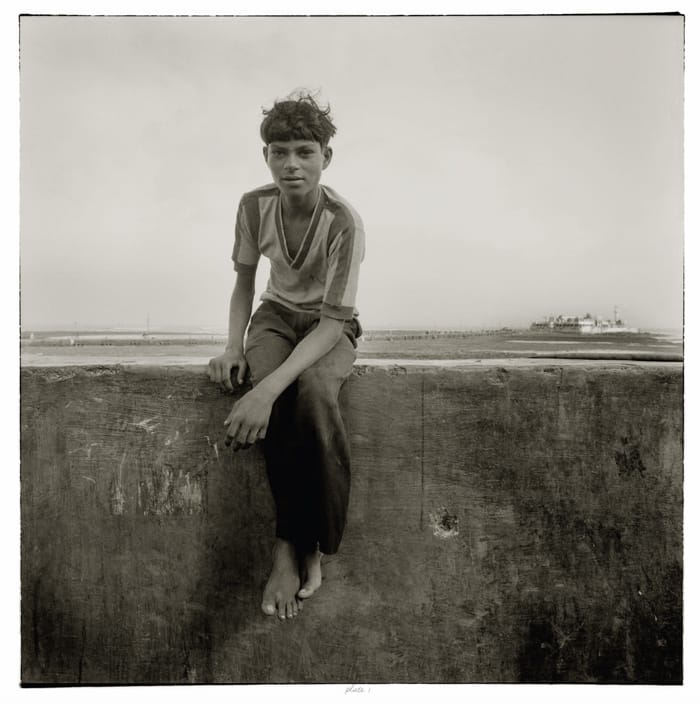

The work of Joseph McGlennon seen here in the Bombay Wall series is nothing like the creatively bankrupt photography so often paraded under the empty banner of “travel photography”.

Throughout McGlennon’s images he displays a rare sense of understanding, compassion and artistry. Photography has been a passion for Joseph since he was a teenager and over the last 20 years he has developed a depth of visual literacy that imbues his images with a beauty and complexity that rewards repeated viewings.

For as the eminent art critic Robert Hughes once said the difference between average art and great art is the difference between impact and resonance.

The images in Bombay Wall are no one line jokes that trade on the initial impact of the exotic then fade in interest as their quirkiness evaporates with familiarity.

Perhaps the key to understanding this work lies in their almost stage-like quality. In visiting the same stretch of wall over four years, McGlennon has had the opportunity to bestow as much care and observation on the stage as he does the players that populate it.

In discussing his ambient music series the musician Brian Eno talks about the idea of sitting beside and watching a slow moving river — it is constantly changing as much as it appears to remain the same.

By maintaining the constant of the wall and letting the power of daily life flow through each image, McGlennon shows us a world that does not balance on the single fragile point of “otherness”, but rather he seeks to draw us as viewers into a space that encompasses humanity instead of exploiting it as novelty.

There are interesting parallels between McGlennon’s images of land and water and those of Joel Meyerowitz and his “Cape Light” series. Meyerowitz photographed the same stretch of beach under varying lighting conditions. McGlennon shows an astute awareness of the nuances that underpin the changing light and atmosphere of his scenes. Shifting subtleties of light and wind on water dance entrancingly across his backdrops, changing with each hour of the day while in the foreground the people of Bombay make their entrances and exits. For me this is where McGlennon’s work hits its stride. Echoes of the European portraiture of Paul Strand and the heartfelt compassion of Peter Hujar’s Sleep and Death pictures reverberate here in Bombay Wall.

Cartier Bresson’s “decisive moment” is reborn in McGlennon’s patience and commitment. Time and time again Joseph captures that split second where the fusion of subject, environment and action fall magically into place revealing the universality of the human condition. Indeed that is what is compelling about our journey through this book, it is that moment when we recognise ourselves in these images. Love and loneliness, humour and pain, the strange, the dramatic and the everyday swim intoxicatingly throughout Bombay Wall in combinations that speak to us in terms both familiar and strange.

In making these images McGlennon has maintained a rare vision that is always inclusive of a society that is never reduced to a stereotype. Look closely at the gestures on display in these photographs, they carry with them all the grace and beauty of the drama and comedy that is life. His photographs are powerful examples of the ways in which art can lure us into worlds where the questions reverberate with as much force as do the answers.

Mark Kimber

Head of Photography, South Australia School of Art, University of South Australia

[1] A New History of Photography, Konemann, 1998, p. 166