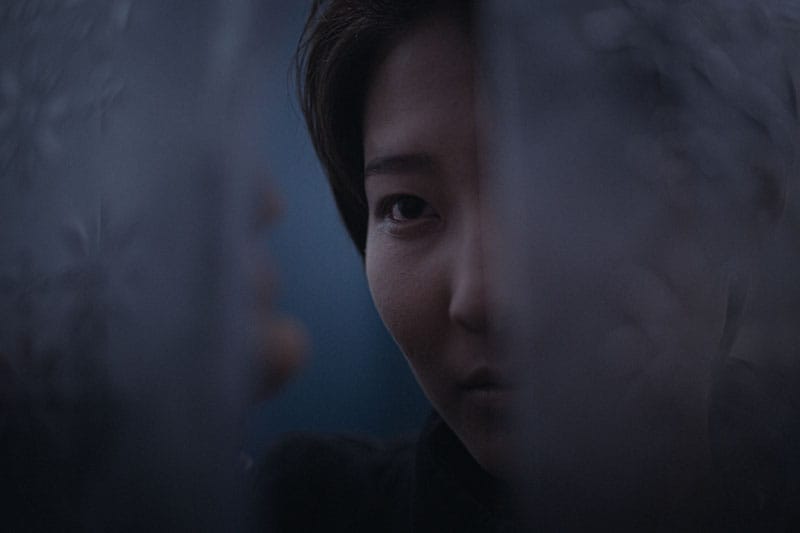

There is an ineffable distinction between being seen and being watched – and nowhere is this distinction more keenly felt than by the Chinese LGBTQIA+ community. A community that photographer François Silvestre de Sacy set out to represent on their own terms in his series Are you recording?, as he explains;

Homosexuality is no longer a crime nor considered a mental illness [in China]. Still, people were hesitant to be involved in this project and reveal their identities. Anonymity and obscurity are a way of life.

For many of my subjects, I was a loophole, a fleeting gateway of expression. I became a confessional of secrets, fears and stories. Apart from disclosing sexual orientation, the subjects also shared thoughts about their country and hopes for their futures.

Some dream of leaving the country, but that is not an option for those who cannot leave family behind. In China, many of the subjects are married and live another life in secret. They find an escape in Taiwanese nightclubs, which offer more freedom than the limited nightlife in Shanghai.

As a result, François’s project is an enigmatic kaleidoscope of dim hallways, blinding neon lights, quick touches, blurred faces and dark club corners – the hidden places where Chinese queer people no longer have to hide.

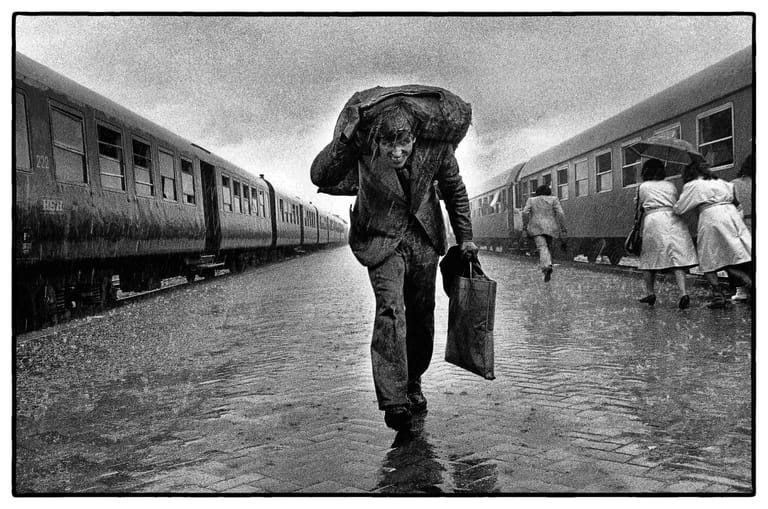

What first brought you to photography?

When I was about 10, my father took a picture of my sister and me, a picture with a great composition that he was really proud of. The joy he felt was contagious. I realised how powerful images could be. And I slowly started to create my own.

How would you describe your photographic practice?

My work mainly focuses on exploring the streets and documenting people’s lives and struggles. I’d like to give greater visibility to those who are invisible, in my own way.

Photography has become an essential tool for the queer community as a means of self-representation and exploration. Why do you think this is?

Photography is key for the LGBTQ+ community and to minorities in general. Photos are testimonies. Testimonies of what happened, of what people are going through, of their identity. Many members of the queer community want and need to speak up to escape the suffocating bubble they live in. Images are the perfect medium to catch someone’s attention as they can say things in ways words cannot.

“Photos are testimonies. Testimonies of what happened, of what people are going through, of their identity.”

You said about your series “Homosexuality is no longer a crime nor considered a mental illness. Still, people were hesitant to be involved in this project and reveal their identities. Anonymity and obscurity are a way of life.” Can you talk about your experience shooting this series and how you went about getting the LGBTQIA+ community to trust your representation of them?

It turned out to be much easier to approach people in bars, physically, than online, as the internet can be monitored and raises suspicions. My project was well received and generated interest. I didn’t try to convince anyone, but rather to make them want to tell their stories, open up and be guided by my camera. We talked a lot, about their homosexuality but not only that – about China in general, about their perceptions of the whole system in place, about their dreams. I suppose listening to them, showing real interest, allowed me to earn their trust. For some of them, there was a real need to get things off their chest. Ryan, for example, wanted his voice and story to be heard so much, even though he didn’t want his whole face to clearly appear in my photos. But unfortunately, he then asked me a few months later not to publish his pictures, following the enactment of the Hong Kong national security law. The photo that, in my view, best represented him was a close-up of his eyes, and he feared the Chinese authorities might be able to track him down through their facial recognition technology. A common fear and distrust in China.

“I suppose listening to them, showing real interest, allowed me to earn their trust. For some of them, there was a real need to get things off their chest.”

The subjects of your images are simultaneously highlighted in neon lights and hidden in shadows, seeming to allude to the duplicity of who they are during the day and who they are at night. Could you speak about your use of shadows, close-up, colour and other visual elements in this series?

I didn’t plan to make this series at night, it just came up that way naturally, through conversations and encounters. A few of the subjects of my images try to live their sexuality more freely, although they use escape routes from the confines of their society. And it became obvious to me that I somehow wanted to show their kind of Dr-Jekyll-and-Mr-Hyde situation. Close-ups are meant to highlight some specific features and ambivalent traits of the people I met: doubts, fears, self-acceptance, willingness to be themselves, provocation, desire for freedom, exclusion, resignation, hopes. The atmosphere, colours and darkness of Chinese cities proved to be a perfect setting. And in some sense, the streets and their billions of cameras were a way for them to stand up despite being in a public space.

Who is a big inspiration of yours?

Wong Kar-wai. I keep watching and watching his films and I’m still as fascinated as I was on day one. The guy is a genius.

See the Are you recording? exhibition here

You may also be interested in the following interviews:

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

0 Comments