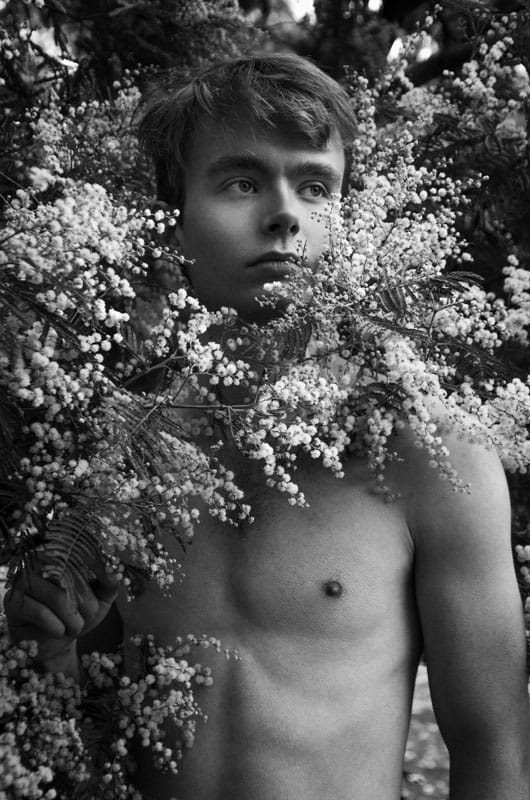

Thanh’s striking black-and-white photographs reference classical portraiture and sculpture dating back to antiquity – in these images, he reappropriates Western ideals of the heterosexual male body – with one major adaptation: represented are the bodies of gay men, at once vulnerable and resilient.

In my garden, the trees are changing asks us to rethink our views of the nude male figure, sexual attraction and representations of the queer body, by alluding to the visual language of classical art while paying homage to the works of pioneering LGBTIQ+ artists who forged the way.

What first brought you to photography?

When I started my degree in photography, I knew very little about the medium as my background is in art, but the concept of ‘painting with light’ was fascinating and it made sense as a bridge between the world of the Old Masters and the modern-day artists. In hindsight, that was a great place to begin my journey, to have carried no preconceived notion of the way photography works as an artistic discipline or the how and why of the craft.

“…the concept of ‘painting with light’ was fascinating and it made sense as a bridge between the world of the Old Masters and the modern-day artists…”

Photography has become an essential tool for the queer community as a means of self-representation and exploration. Why do you think this is?

Photography, at its most basic level, is a way to communicate. The works of self-identified queer artists have also become tools in the fight for equality and coerced political as well as social change; progress has been made within the last 50 years in regards to tolerance and civil rights, but members of the LGBTIQ+ community continue to experience discrimination in many aspects of life. As a self-identified gay man, my photographs become my voice in addressing some of these issues, enabling their visibility. Also, when seen as a collaboration, each of the men whom I have photographed contributes to the narrative and strengthens a simple message at the core of my practice: They’re here. They exist; I’m here. I exist. Together, we continue to sow and cultivate the seeds of change.

“…They’re here. They exist; I’m here. I exist. Together, we continue to sow and cultivate the seeds of change…”

In your series, In my garden, the trees are changing, you capture gay men in a sensual way that is at odds with a cis-gender/heterosexual idea of sexual machismo. You celebrate the male body for its sensual beauty, its fluidity, strength and fragility. Could you speak to your creation of the queer male body as a subversive sexual subject in your work?

Open any queer publication, going back to the 50s and the early physique magazines (whose target audience were gay men) and you will see muscle bound gods. In the early days of protests and sexual liberation, the physical heteronormative traits of masculinity were appropriated by some gay men as a counter-attack to the assumption that gay men are effeminate and weak. A new school of thoughts came into existence where macho is the beau ideal, then, a way of living and being manifested from the fetishization of hyper-masculinity, which were popularized in such works as Tom of Finland by Finnish artist Touko Valio Laaksonen. These ideals of manliness persist. I question and challenge this superficial, non-inclusive, hyper-sexualized and hyper-masculine monotonous image. Not all men are heroes or fighters. Not all men are strong, bronzed and sculpted. Not all men are sexual. The attributes of masculinity cannot be defined for all individuals. In my practice, I continually analyze these ideals.

“Not all men are heroes or fighters. Not all men are strong, bronzed and sculpted. Not all men are sexual. The attributes of masculinity cannot be defined for all individuals.”

In much of your work, you capture group scenes, in which male figures work together to create intricate compositions with their bodies. Could you speak about how you go about choreographing and capturing these scenes and the importance of capturing men interacting with each other in these intimate vignettes?

None of the men I’ve photographed are professional models. They are friends, lovers, and companions; a few are strangers whom I’ve met one afternoon and never see again. But my relationship with these men, fleeting in some circumstances, and their connections with one another become a part of the narrative within each frame that is true and consistent in relation to the larger body-of-work. Within the four corners of an image, I have control of time, space and the physicalities of bodies and landscapes, of lines, shapes and forms. All of these elements, when they come together, create photographs with a strong compositional foundation and, conceptually, communicate abstract thoughts and ideas.

“None of the men I’ve photographed are professional models. They are friends, lovers, and companions; a few are strangers whom I’ve met one afternoon and never see again.”

Could you speak about your use of black-and-white photography?

I love old, faded photographs and I like looking into the past through the lens of those who have inspired me. These are a few reasons why I shoot in B&W and also on film. It is not just the aesthetics of B&W or the wonderful mechanics of analogue photography but a physical act of reaching out into the past, to forge a connection to those pioneering queer artists who have laid the path for future generations, to connect to the strangers and foreign lands in their works, and to situate what I do somewhere along the timeline of then and now.

Who is a big inspiration of yours?

Wilhelm von Gloedon

See the In my garden, the trees are changing exhibition here

You may also be interested in the following interviews:

0 Comments